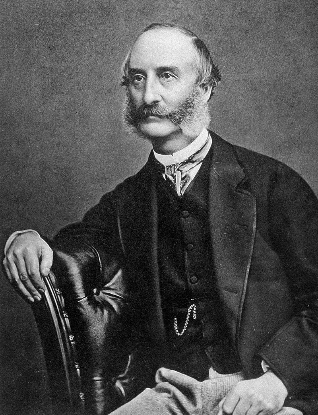

Edmund Alexander Parkes

Edmund Alexander PARKES 1819-1876

Edmund was born on 29th march to William and Frances nee Byerley.

In 1860 an Army Medical School was established at Fort Pitt, Chatham, and Parkes, who had been consulted on the scheme by Sidney Herbert as Secretary of State for War, accepted the chair of hygiene. University College appointed him emeritus professor, and a marble bust of Parkes was placed in the museum.

At the Army Medical School at Chatham Parkes organised a system of instruction. In 1863 the school was transferred to the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley. Parkes was constantly engaged in protracted official inquiries connected with hygiene. He was a member of General Henry Eyre's "Pack Committee", which substituted the valise equipment for the cumbrous knapsack. In 1863 he was appointed by the crown to the General Medical Council, in succession to Sir Charles Hastings. He was a member of the council of the Royal Society, where he was elected a Fellow in 1861; and he was elected to the senate of the University of London.

Parkes died on 15 March 1876, at his residence, Sydney Cottage, Bittern, near Southampton, from tuberculosis, and he was buried by the side of his wife at Solihull. In 1850 he had married Mary Jane Chattock of Solihull. She died, after severe suffering, in 1873, without issue.

At Netley, a portrait of Parkes, by Messrs. Barraud & Jerrard, was in the anteroom of the army medical staff mess; a triennial prize of seventy-five guineas, and a large gold medal bearing Parkes's portrait, was established for the best essay on a subject connected with hygiene, the prize to be open to the medical officers of the army, navy, and Indian service of executive rank, on full pay; and a bronze medal, also bearing the portrait of Parkes, was instituted, to be awarded at the close of each session to the best student in hygiene.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Alexander_Parkes

Edmund Alexander Parkes (1819–1876)

After graduating Parkes decided to enter the Army Medical Service, and he was gazetted assistant surgeon to the 84th (York and Lancaster) regiment in 1842; the reason for his decision to join the army is unknown. After spending three years on tour with the army in Burma and India, he retired to take up a position as assistant physician at University College Hospital, London. But though the duration of his military service was brief, Parkes's firsthand experience of cholera, hepatitis, and dysentery had a profound and lasting impact on his career. Immediately after leaving the army he published several original pieces of research into the aetiology, pathology, and treatment of these diseases. The first was The Dysentery and Hepatitis of India (1846), in which he expressed the opinion that there was a link between the two disorders. The second was a version of his MD thesis, awarded by the University of London in 1846, and published as Researches into the Pathology and Treatment of Asiatic or Algide Cholera (1847). This study confirmed the recent tendency in medical circles to see cholera as primarily a disease of the blood, but it also suggested that respiratory problems caused by disordered blood were ‘the proper and distinctive symptoms of the disease’ (p. 4).

Parkes's purpose in elucidating the pathology of cholera was to improve diagnosis and to pave the way for future research, should cholera return to Britain. In the short time between the publication of his thesis and the next epidemic of cholera in 1849, Parkes had established himself as an authority on the disease. Indeed, the newly formed General Board of Health commissioned him to conduct an investigation into the first few cases of cholera as they appeared in London. Parkes's brief was to consider the question of the contagiousness of cholera—whether or not it was capable of being spread from person to person. Parkes had already expressed his opinion, on the basis of observations made in India, that this was not the case. The London epidemic only confirmed his view, since he was unable to find any connection at all between the cases he examined. Parkes was a believer in what he termed a ‘modified’ theory of contagion, which held that there was a specific agent causing cholera, but that certain atmospheric and other local conditions were necessary if it was to assume epidemic proportions. Parkes's emphasis on the local causes of cholera was very much in line with that of the General Board of Health, which stressed that cholera was primarily caused by filth and poor sanitation.

Parkes's professional standing was now such that he was promoted in 1849 to the post of first physician of University College Hospital and to the chair of clinical medicine at University College. He was barely thirty years of age. In the coming years he took on still more professional responsibilities, including the editorship of the British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review between 1852 and 1855. He also found time to write a number of original articles on diseases of the heart and skin, and the effects of alcohol upon health. In 1855 he was chosen as Goulstonian lecturer to the Royal College of Physicians, and spoke on the subject of pyrexia. Little is known of his private life at this time, except that he was married on 1 August 1850 to Mary Jane (d. 1873), daughter of Thomas Chattock, a solicitor of Solihull.

Had it not been for the Crimean War of 1854–6, it is unlikely that Parkes would have returned to the field of military medicine, an area in which he was to make some of his most important contributions. However, public outrage at the poor medical arrangements made for British soldiers in the Crimea led to several initiatives to reform and expand hospital accommodation, including the shipment of an entire hospital designed and prefabricated by the engineer Sir Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and the War Office requested that Parkes superintend the formation and management of the hospital established (on Parkes's recommendation) at Renkioi, in the Dardanelles.

After the war Parkes became involved in an advisory capacity in the reform of military medicine and, in particular, in the creation of an army medical school. He was induced to leave his post at University College to take the chair of military hygiene at the school, which was established in 1860 at Fort Pitt, Chatham, and he continued to hold this post after the school moved to Netley, near Southampton, in 1863. Parkes was an immensely popular teacher, beloved by students and staff alike. A particularly full account of his influence was given by one of his more prominent pupils, William Jenner. He also remained an active researcher, and was regularly engaged in investigations into the suitability of military rations, clothing, and equipment. In addition to this work he pursued independent research into other subjects such as human excretion. His distinguished record in research earned him a fellowship of the Royal Society in 1861.

However, it is for his work as a hygienist that Parkes is most usually remembered and, in particular, for his Manual of Practical Hygiene: Prepared Especially for Use in the Medical Service of the Army, which was first published in 1864. The Manual, which went through eight editions (the last in 1891), was regarded by military medical services around the world as the definitive text on the subject. It was also used extensively by civilian sanitary officers, especially in British India and the colonies. The Manual made use of the latest scientific research to inform practical sanitation and clearly illustrates Parkes's ‘contingent-contagionist’ position on the causation of diseases such as cholera. It outlines measures to prevent the entrance of disease agents into the human body (directing attention to the contamination of food and water supplies, for example), while stressing the need for more general environmental controls, including the removal of filth and refuse. Like most of his contemporaries Parkes also believed that an individual's daily habits played an important role in either guarding against or predisposing to infection. In a phrase which exhibits something of his religious convictions, as well as his approach to hygiene, Parkes wrote of the need to ‘combine the knowledge of the physician, the schoolmaster, and the priest’, and to ‘train the body, the intellect, and the moral soul in a perfect and balanced order’ (p. xvi).

Although Parkes was an ardent advocate of ‘state medicine’, with its preventive legislation, and of utilizing the very latest techniques afforded by science, he had not abandoned older views of hygiene, which emphasized the importance of bodily equilibrium. His ardent belief in the need to regulate body, mind, and environment was expressed very clearly in his last two works, both of which were published shortly after his death. The first of these, a pamphlet written for the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, On Personal Care of Health (1876), was directed at the layperson and outlined the modes of life most appropriate to the preservation of health at different ages. The second work, Public Health (1876), dealt exclusively with ‘state medicine’, and is notable chiefly for its advocacy of sanitary reform in rural areas and a stricter interpretation of existing sanitary legislation.

The last months of Parkes's life were spent in a state of continual ill health, which was noted with concern in all the leading medical journals. Parkes finally succumbed to what was later revealed to be acute tuberculosis, though he had suffered persistently from respiratory problems and phlebitis since 1860. He died on 15 March 1876 at his home, Sydney Cottage, St Mary Extra, Bitterne, Southampton, aged only fifty-seven, and was buried on 21 March at Solihull beside his wife, who had died three years before. Friends who had gathered at his bedside said that Parkes accepted death peacefully and bravely, unshaken in his belief that there was an afterlife. He and his wife left no children, but his nephew, L. C. Parkes, followed in the footsteps of Parkes as a writer on hygiene and public health. After his death members of the Army Medical Service contributed generously to a memorial fund which established the Parkes memorial prize, awarded triennially for the best dissertation on military hygiene. Although he had never received the knighthood that many of his contemporaries felt he deserved, Parkes's professional standing was indicated by his membership of the General Medical Council, the council of the Royal Society, and of the senate of the University of London.

Parkes was an uncommonly popular man, respected as a scientist and a practical hygienist, and for what the British Medical Journal called his ‘wisdom, moderation and gentleness of character’. He was regarded by many contemporaries as the ‘father of modern hygiene’ and as a pivotal figure in the development of military medicine.

Oxford DNB

Mark Harrison, ‘Parkes, Edmund Alexander (1819–1876)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21352, accessed 28 May 2017]