How to research a soldier who served in the British Army in WWI http://www.researchingww1.co.uk/british-soldiers-ww1

What happened to the soldiers who died in the War?

From Charlie Kinkead on the World War One facebook page.

Almost a million British soldiers died in the Great War. Some died alone, killed by a chance shell, grenade or bullet; many died together as they attacked or defended against attack. Thousands of men died of wounds they had suffered, at the medical facilities along the casualty evacuation chain. Many died of illnesses or accidents. This is all well-known and well documented: but what actually happened to them after they died?

Men who were killed in the fighting area

The varying nature of mens deaths in the front line and the specific conditions at the time of their death meant that their ultimate fates differed widely. For example:

Some men would have been identifiable and probably buried close to the front line. This would have included, for example, men killed by a sniper or shell explosion whilst holding a trench or on a road close behind the lines; men dug out of a collapsed mine, trench, sap or dug-out; and men dying of wounds having begun their evacuation, but whilst still in their Battalion or Brigade area. These men would be identified by comrades, NCOs or officers.

- some men would have been less easily identifiable, but probably buried in cemeteries or burial plots still quite close to the firing line. This might typically have included those men who had attacked and been killed or died of their wounds, but whose bodies could not be brought in because the place they were lying was under fire. Eventually when the fighting moved away, their bodies would be buried if possible. In this category too would be men who died in a successful advance, whose bodies would be cleared by units other than their own. Identification would be through pay books, tags, and other physical means by men who did not know the individuals.

- some men would be unidentifiable, if the damage to them was such that they ceased to exist as a body or where any form of identification had been lost. Fragments of men, once found, would be buried if possible.

many men were simply not found, although post-war battlefield clearance (see below) reduced the total of missing.

Many thousands of small burial plots were created on or very close behind the battlefields. They were often damaged by shellfire, and in 1918 many were over-run first by the advancing enemy and later by the Allies pushing eastwards again. Plots were destroyed as the ground was shelled, and the locations of many graves that had been registered and known about were made uncertain.

Men who died on the casualty evacuation chain

Cemeteries were created at most of the places where the Casualty Clearing Stations and the less mobile Base Hospitals were located. These cemeteries were rather more orderly in terms of layout, tended to be rather larger due to the concentration of death, and some had the benefit of attention to the grass and flowers around the graves. In most cases, the man was identified and usually his burial was attended by a Chaplain. Some of the these cemeteries suffered from shellfire or other damage, particularly as those laid out in 1914-1917 were overrun by the enemy and then the counter-attacking Allies in 1918.

How the next of kin were informed

Once the man was confirmed dead, the next of kin were informed of the terrible news. Officers next of kin were informed by telegram:

Official enquiries would be made via neutral channels to see if the man was in enemy hands as a prisoner of war, or that the enemy had definite knowledge that he was dead. After six months had elapsed with no news from this enquiry, the next of kin would be contacted to see if they had received any further information from friends or comrades. If not, the man's death would be presumed to have taken place on the last day he was known to be alive.

The Graves Registration Committee

In the earliest days of the war there was no organisation responsible for the marking, recording and registration of soldiers graves other than the man's own unit. In October 1914, a Mobile Ambulance Unit provided by the British Red Cross and headed by Fabian Ware (it had previously been operating as a medical unit with the French Army) began to undertake these duties on a voluntary basis. Soon enough, the unit found that the need for graves registration so large, and the growth of army medical units so rapid, that is was able to concentrate solely on this task. Prior to 11 November 1918, graves registration was the responsibility of the army in the field. The following information is extracted from the Adjutant Generals Instructions to the BEF:

The establishment of permanent graves was afforded by the French Government by law on 29th December 1915. France provided land that would be maintained in perpetuity for British war dead. The Director of Graves Registration and Enquires (DRG&E), as representative of the Adjutant General, had sole and global responsibility to work with the French Government for the establishment of these cemeteries. The office of the Director of Graves Registration and Enquires was located in Winchester House, St James, London. Below this office each Field Army had a Deputy Assistant DRG&E. Grave registration in the field fell squarely on the shoulders of the unit Chaplains. They were responsible for filling out the proper form (AF W3314) that included the information about the grave, and forwarding to both the DADGR&E and the DAGGHQ 3rd Echelon. Information submitted included map references using the 1/40000 or 1/20000 trench maps, or detail descriptions of localities on the back of the form, in addition to the usually expected basics such as the man's name, unit etc. He was also responsible for the marking of the graves. However, many dead were interred into already authorised cemeteries. In this case special instructions were issued as each authorized cemetery was usually under the care of a Graves Registration Unit. The actual interment of graves was up to the unit. The term “unit” could mean many things; internment by the unit of the actual casualty, internment by Casualty Clearing Stations, Field Ambulances, General Hospitals, Graves Registration Units etc. Grave registration units were non-permanent units, that is some lucky unit was detailed to perform that task and it could be any one. Basically graves registration was the responsibility of the unit responsible for the casualty or the unit finding the casualty.

How next of kin were informed of place of burial

The work of the Graves Registration Units allowed a system to be set up whereby the next of kin could be informed of the place of burial of the soldier.

Post-war clearance of the battlefields

After the war, certain parts of the battlefields were taped out into grids and searched at least six times. This activity went on well into the 1920's, on a large scale. The search parties (Exhumation Companies) did not dig over all of the land marked out by the grid. Instead, they looked for clues that indicated that a body or bodies could be buried there. For example: rifles or stakes protruding from the ground bearing helmets or equipment; partial remains and equipment that had come to the surface; small bones and pieces of equipment brought to surface near to rat-holes; discolouration of grass, soil or water. (Grass was a more vivid colour where bodies were buried and water turned a greenish-black). Once a grid had been searched and possible bodies marked then the gruesome task of exhumation began. Remains once discovered were put onto cresol soaked canvas for a careful identification. If any uniform remained, pockets were searched and badges and buttons identified. If a Scottish soldier was found, the tartan was recorded. Next they looked for identification discs and personal effects: watches sometimes had useful had inscriptions, for example. Sometimes knives, forks and spoons that had been placed down the puttees carried the man's name, initials or number. Webbing was checked because that also often had soldiers names and numbers stencilled on. If the remains were deemed to be an officer (Bedford cord breeches and privately bought army boots being a good indication) and the skull or jawbone was intact then a dental record of the teeth, fillings, false ones etc was also made in an effort to confirm the identification of the man. The remains would then be taken to one of the cemeteries that was open for burial. Thus many of the small wartime burial plots were expanded with the post-war additions; indeed many bodies were exhumed from small cemeteries and concentrated into larger ones. Those remains that could not be identified were buried as an unknown soldier.

Human remains are still being found on the battlefields to this day.

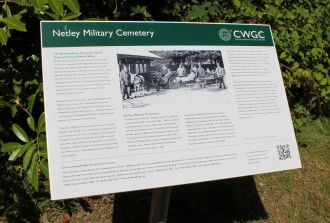

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The war time Graves Registration Units eventually developed into the Imperial War Graves Commission and henmce to today's Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Funded in proportion of their dead by Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, India and other states, it carries out the care and maintenance of the cemeteries and memorials of not only WW1 but all subsequent conflicts. Most visitors to the battlefields never cease to be impressed by the standard to which they are kept, and long may it remain this way.

The Great War Memorial Plaque

The Memorial Plaque was issued after the First World War to the next-of-kin of all British and Empire service personnel who were killed as a result of the war.

The plaques (which could be described as large plaquettes) were made of bronze, and hence popularly known as the "Dead Man’s Penny", because of the similarity in appearance to the somewhat smaller penny coin. 1,355,000 plaques were issued, which used a total of 450 tonnes of bronze, and continued to be issued into the 1930s to commemorate people who died as a consequence of the war.

Description

It was decided that the design of the plaque, about 5 inches (120 mm) in diameter and cast in bronze, was to be picked from submissions made in a public competition. Over 800 designs were submitted and the competition was won by the sculptor and medallist Edward Carter Preston using the pseudonym Pyramus, receiving two first place prizes of £250 for his winning and also an alternative design.

Carter Preston's winning design includes an image of Britannia holding a trident and standing with a lion. The designer's initials, E.CR.P., appear above the front paw. In her outstretched left hand Britannia holds an olive wreath above the rectangular tablet bearing the deceased's name cast in raised letters. Below the name tablet, to the right of the lion, is an oak spray with acorns. The name does not include the rank since there was to be no distinction between sacrifices made by different individuals. Two dolphins swim around Britannia, symbolizing Britain's sea power, and at the bottom a second lion is tearing apart the German eagle. The reverse is blank, making it a plaquette rather than a table medal. Around the picture the legend reads (in capitals) "He died for freedom and honour", or for the six hundred plaques issued to commemorate women, "She died for freedom and honour".

They were initially made at the Memorial Plaque Factory, 54/56 Church Road, Acton, W3, London from 1919. Early Acton-made plaques did not have a number stamped on them but later ones have a number stamped behind the lion's back leg.

In December 1920 manufacture was shifted to the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. Plaques manufactured here can be identified by a circle containing the initials 'WA' on the back ( The "A is formed by a bar between the two upward stokes of the "W") and by a number stamped between the tail and leg (in place of the number stamped behind the lions back leg).

The design was altered slightly during manufacture at Woolwich by Carter Preston since there was insufficient space in the original design between the lion's back paw and the H in "HE" to allow an "S" to be inserted to read "SHE" for the female plaques. The modification was to make the H slightly narrower to allow the S to be inserted. After around 1500 female plaques had been manufactured the moulds were modified to produce the male version by removing the S.

The plaques were issued in a pack with a commemorative scroll from King George V; though sometimes the letter and scroll were sent first.

Wikipedia

Commonwealth War Graves

Link for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site:

In order to qualify for a Commonwealth War Grave, a Commonwealth man or woman must have been serving in the military at the time of their death. They must have died between these dates:

First World War - 4th August 1914 to 31st August 1921

Second World War - 3rd September 1939 to 31st December 1947

Have a look at the In From The Cold website where you can report graves that qualify for a CWG headstone which do not already have one.

If you are researching a grave from Australia, New Zealand or Canada you may find quite a lot of details about the deceased online. Try typing their name into google and quite often you will find the name you are looking for in the government web sites for the respective countries. Documents can include embarkation details, hospital reports, next of kin information, sometimes letters etc. I wish it was the same for all the commonwealth war graves.

The Origins of the Last Post

The Last Post was first published in the 1790s, just one of the two dozen or so bugle calls sounded daily in British Army camps. "At that time soldiers didn't have wristwatches, so they had to be regulated in camp," says Colin Dean, archivist at the Museum of Army Music in Kneller Hall. "They had to have a trumpet call or a bugle call to tell them when to get up, when to have their meals, when to fetch the post, when to get on parade, when to go to bed and all other things throughout the day."

The soldier's day started with the call of Reveille, and came to a close with the First Post. This indicated that the duty officer was commencing his inspection of the sentry-posts on the perimeter of the camp. The inspection would take about 30 minutes, and at the end there would be sounded the Last Post, the name referring simply to the fact that the final sentry-post had been inspected. For decades this was the sole use of the call, a signal that the camp was now secure for the night, closed till morning.

It was not until the 1850s that another role began to emerge. It was an era when many military bandsmen, and most bandmasters, were civilians and were under no obligation to accompany their regiments on overseas postings. So when a soldier died in a foreign land, there was often no music available to accompany him on his final journey. And, necessity being the mother of invention, a new custom arose of charging the regimental bugler to sound the Last Post over the grave. The symbolism was simple and highly effective. The Last Post now signalled the end not merely of the day but of this earthly life. And, as the practice developed - back home now as well as abroad - it was then followed by few moments of silent prayer and by the sounding of Reveille, the first call of the day, to signify the man's rebirth into eternal life.

A further dimension was added in the first years of the 20th Century. The end of the Boer War saw the rise of war memorials across the country, some 600 of them. This was a break with the past. The traditional British way of commemorating a victory was to erect a statue to the general or the commander. But these monuments listed the names of the dead, both officers and other ranks, the men the Duke of Wellington was said to have called "the scum of the earth".

There was a new mood of democracy abroad and the war memorials reflected this. And every time a memorial was unveiled, it was to the sound of the Last Post being played, now the symbol not only of death but of remembrance.

By the time that World War One broke out in 1914, the Last Post was already part of the national culture. During the war, it was played countless times at funerals in northern Europe and other theatres, and it was played at funerals, memorials and services back home. It was already becoming a familiar sound, but with mass enlistment and then conscription, the walls that had long existed between the civilian and the soldier broke down completely, and a piece of music that had once belonged exclusively to military culture was adopted by a wider society.

HG Wells said this was "a people's war", and the Last Post became the people's anthem.

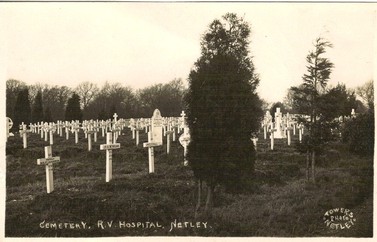

The plaque on the Cross of Sacrifice at Netley says there are 721 casualties from WW1 and 36 from WW2 comprising of:

United Kingdom 558

Australia 49

Canada 42

New Zealand 12

South Africa 6

Undivided India 5

Belgium 15

Poland 1

Austria 1

Germany 68

According to the burial records, the first Commonwealth War Grave was for 2822 Lce Sgt CURLEY who was in the Irish Guards and died on 20th August 1914 age 25.

Burial record 786 Roman Catholic. His grave is on the right hand side, on the hill just as you enter the cemetery, near the top.

********************************************************************

The Commonwealth War Grave Commisiion site has all the Commonwealth graves listed from all around the world.

In the United Kingdom, there are 12401 cemeteries with memorials and graves from WWI and WWII.

From these, 9384 cemeteries have WWI burials and here

are the top 6:

1st Brookwood Cemetery more than 1601 in WWI and more than 3470 from WWII

2nd Haslar Cemetery more than 1359

3rd Manchester Southern Cemetery 1265 from WWI and WWII

4th Gillingham (Woodlands Cemetery) Kent 1233

5th Aldershot Military Cemetery 857

6th Netley Military Cemetery 772 from WWI and WWII

|

For the Fallen by Laurence Binyon

September 1914 |

The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware.

Gave, once her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blessed by the suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts a peace, under an English heaven.

Rupert Brook 1887-1915

For the sailors who don't come home........

“In Ocean waves no poppies blow

No crosses stand in ordered in row

Their young hearts sleep beneath the wave

The spirited, the good, and the brave,

But stars a constant vigil keep,

For them who lie beneath the deep,

‘Tis true you cannot kneel in prayer,

On a certain spot and think he’s there

But you can to the ocean go

See whitecaps marching row on row;

Know one for him will always ride,

In and out with every tide,

And when your span of life is passed

He’ll meet you at the ‘Captain’s Mast’

And they who mourn on distant shore,

For sailors who will come home no more,

Can dry their tears and pray for these

Who rest beneath the heaving seas,

For stars that shine and winds that blow

And whitecaps marching row on row

And they can never lonely be,

For when they lived they choose the sea.”

Eileen Mahoney