WWII

Hampshire Advertiser 11th May 1940 Blood Donors needed.

The American's arrival

Snag 56 by Henry W Hudson Captain (MC) USNR

1946

During the last week of December, 1943, Captain C. J.Brown (MC) USN was notified by telephone that the SurgeonGeneral wished to see him. In Admiral Mcintire's officehe was informed that he was

to command a hospital located at Netley, which Captain Brown located later in an encyclopedia.

Between January thirtieth and February thirteenth, Captains Brown and Miller and Ensign Breathwit established temporary headquarters in the old family hospital, which had the virtue of one warm

room, and familiarized themselveswith buildings, grounds, and the physical state of the establishment.

Thirteen officers and seventy-five men arrived on the thirteenth, cold, hungry, and fatigued; on the nineteenth a second group and, on the twenty-sixth, the last group arrived.

The last was less hungry but colder than the first.

Between the seventeenth and the twenty-second the nurses arrived. Thus on the twenty-sixth the unit was assembled and ready to take over.

Army personnel moved out as the Navy came in and assumed the several duties. It was arranged that Snag 56 (we still had no other designation would relieve on February twenty-eighth but the log

indicates that a Navy watch was established on the twenty-second.

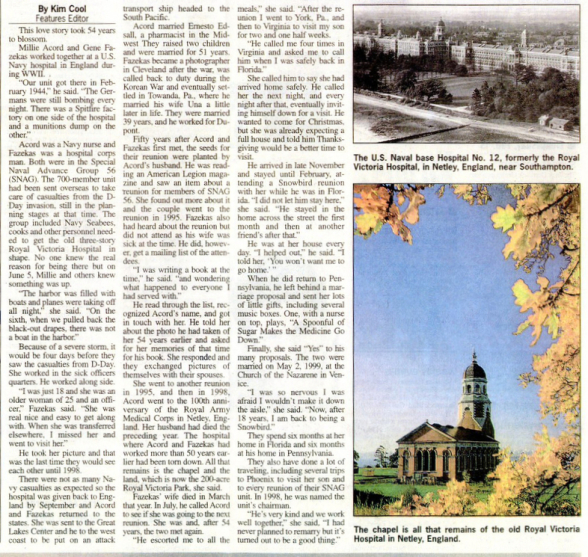

UNITED STATES NAVAL BASE HOSPITAL "#12

Despite the fact that we "took over" from the Army on February 28 and were designated as a Base Hospital on April first, it was apparent that there was much to be accomplished.

We thought at times it would have been better to close the Royal Victoria and erect a mobile hospital on the playing fields.

The terms of agreement stated- "subject to - the following reservations - only serviceable stores will be handed over."

Little was handed over and the serviceability of that was open to question. In addition to disrepair, lack of heat and lighting, there was insufficient messing gear, only one galley was in

commission and smelled dreadfully, we semiclosed spaces behind the Tiuty Bunks were filled with cartloads of trash, discarded dressings, etc. One anesthetic apparatus could not be used, the second

had many leaks and mechanical defects.

There were only two knife handles, little suture material, very little alcohol, no distilled water, no sulphur compound for intravenous use, and only thirteen units of plasma. Sufficient tubing,

glassware and needles to give infusions were not at hand. Instruments were antiquated, mechanically defective, and dull.

There was insufficient linen, few hospital type or surgical beds, and, for some weeks, no x-ray film or codeine. But there were 325 patients

with a steady flow of admissions thereafter. Material supply was a problem.

with a steady flow of admissions thereafter. Material supply was a problem.

First we were told that the U.S. Army would supply us with anything we did not have to equip a 1000 bed general hospital. Thus we had to find out what we had, identifying instruments

without a British catalogue and

surveying most of them. Then, without an Army T.B.A., we had to prepare requisitions without the typewriters, paper and carbons necessary. One can't fight a war without typewriters!

surveying most of them. Then, without an Army T.B.A., we had to prepare requisitions without the typewriters, paper and carbons necessary. One can't fight a war without typewriters!

Finally, the Navy was to supplement the Army equipment but the Navy Medical Stores in Exeter was then on paper only. Eventually from these sources and from the hospital at Creveagh we were well supplied although we were still making up deficiencies in June! Mr. Vizard and Mr. West had a difficult job, as did the Chiefs of Service, in procuring equipment and supplies.

Before "D" day we were well equipped and, before that, managed to take care of over 1500 patients without a patient suffering. Mr. Moose and his Commissary crew had to clean thoroughly the

galley and storerooms and procure Army rations by truck ·from Portsmouth, twelve miles away. The First Lieutenant, Mr. Haralson, had his troubles. One little item was to raise and take down 600

wooden black-out screens, in the long passageways, each day. Then there were the lifts to be repaired, lockers and other furnishings to be made, painting, plumbing, installing space heaters, setting

up ice machines and hundreds of other maintenance and construction operations.

At first without typewriters, forms or paper, Mr. Breathwit in Personnel and Mr. Schuster in Medical Records had to handle the paper work of British and U. S. Army and Navy, Coast Guard, Merchant Marine, and civilian patients.

At first without typewriters, forms or paper, Mr. Breathwit in Personnel and Mr. Schuster in Medical Records had to handle the paper work of British and U. S. Army and Navy, Coast Guard, Merchant Marine, and civilian patients.

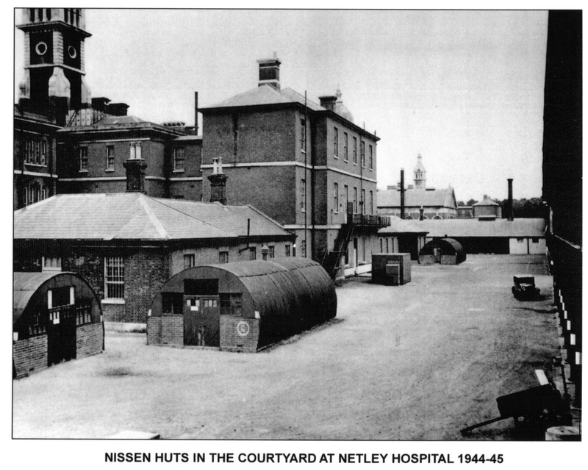

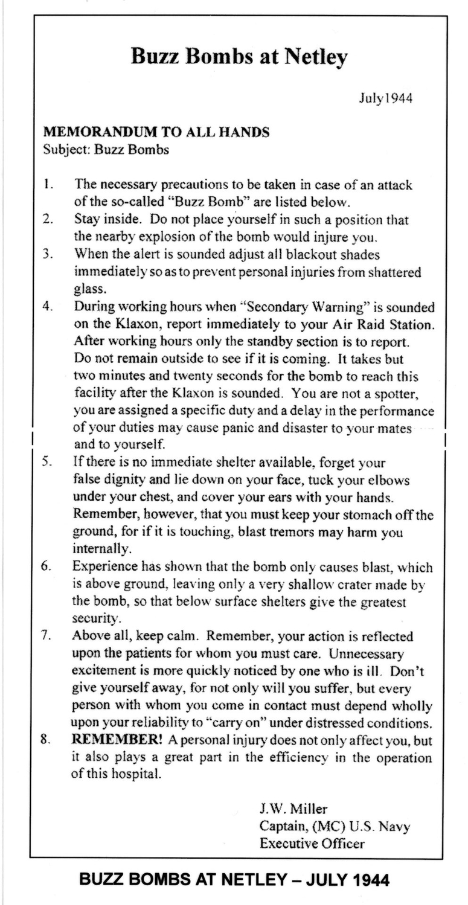

Dr. Kearns, Mr. Nash, and Mr. Louder were responsible for security against fire, air raids, (later buzz bombs), gas defense, liaison with British bomb disposal and A R P, for the disposition of the guard and for intelligence. It must have been an interesting but sleepless job.

Mr. Hilbinger had to provide details for wards, special sections, maintenance, commissary, transportation, records, personnel, security, an armory, Chaplain and Red Cross activities, barbers, storekeepers, M.A. crew, paymaster staff, mate of the day and assistants, color guard, stewards and heaven knows what else in the face of constant requests from all sides for more, or different, or better men. And then he and his crew had to censor the mail of over 700 staff and patients ranging up to 900.

By an all hands effort the hospital was cleaned, equipped, heated, lighted, patients were cared for and recreation provided. Chow was improved. Religious and social services were provided.

C.D.R. and the operating theatres were stocked and the plaster room ran efficiently.

On the third deck an N.P. unit was established, Surgery V and VI, Dental, G.U., EENT, a medical library and a good operating suite were developed. On the second, Burn Wards, Medical I, II, III, and IV and SOQ functioned. On the first deck Orthopedic (Surgery I and II), a plaster room, two chapels, the Shock Room, the triage facility, another operat-ing suite, CDR and Surgery III and IV were arranged as were the Administrative offices.

SNAG 56 AT NETLEY, HANTS

As Seen through the Eyes of One Navy Nurse

HELEN PAVLOVSKY

The Army was still here, for they had taken over from the British until our arrival, and were to leave shortly after we became oriented. We entered through an old door that opened inwardly,

followed by a long trek up four flights of dimly lighted stairs, with a suitcase in one hand and all hope

pointing in the direction of a bath. We could appreciate, in one full glance, the obvious neglect of this antiquated, high ceilinged, strangely constructed place. But with food and a clean bed, probably made by our chief nurse, we were thankful to be here at last. Life had been good to us thus far - we had not been touched by the London air-raids; and here we

were all together again as a unit. We had a job to do!

pointing in the direction of a bath. We could appreciate, in one full glance, the obvious neglect of this antiquated, high ceilinged, strangely constructed place. But with food and a clean bed, probably made by our chief nurse, we were thankful to be here at last. Life had been good to us thus far - we had not been touched by the London air-raids; and here we

were all together again as a unit. We had a job to do!

It was with this strange, confused mixture of emotions; weariness, awe, disappointment, hope, and sheer joy and thankfulness, that I found myself heading down an immense corridor, so cold and unfriendly, to look for the chapel and to find out the time of the masses. Finally, at the foot of what seemed to be a never-ending darkened passageway, stood

the dearest little chapel, set apart and so cosy, it almost didn't belong here. You wondered how it found its little nook in among all this vast, cold, immensity.

The next morning found us on the wards where we met

our medical officers for the first time since we left the ship.

The usual hospital atmosphere was absent. The corridors

and wards were icy cold. There was no means of obtaining

heat except from a two-foot square fireplace which burned

blocks of coal. These were made from powdered coal dust

and oil, compressed into block form. Whenever you remembered

to look, they were out, either from lack of fuel or because

the fuel would not burn. It was against the law to burn

wood, and we were constantly being told to conserve fuel

for tomorrow we might not be able to get any. The first bed,

and perhaps the second, managed to keep warm; how the

others fared must have been by the grace of God alone. But

they were practically all British patients and used to cold

weather. They spoke of their homes which were often entirely

without heat, and felt that what they were getting was

adequate.

The bed linen was soiled, what there was of it, for many

beds were entirely without; and the patients themselves

needed baths and clean clothes. We had practically nothing

with which to work. Those days of improvisation left not

only an ineradicable impression on our minds, but served as

the beginning of a strong attachment to this old place; which

already seemed like ours, for we were rebuilding it. We all

scrubbed and cleaned everything we saw; patients, beds,

equipment, decks and bulkheads. We had to work hard to

get our ship in commission.

and wards were icy cold. There was no means of obtaining

heat except from a two-foot square fireplace which burned

blocks of coal. These were made from powdered coal dust

and oil, compressed into block form. Whenever you remembered

to look, they were out, either from lack of fuel or because

the fuel would not burn. It was against the law to burn

wood, and we were constantly being told to conserve fuel

for tomorrow we might not be able to get any. The first bed,

and perhaps the second, managed to keep warm; how the

others fared must have been by the grace of God alone. But

they were practically all British patients and used to cold

weather. They spoke of their homes which were often entirely

without heat, and felt that what they were getting was

adequate.

The bed linen was soiled, what there was of it, for many

beds were entirely without; and the patients themselves

needed baths and clean clothes. We had practically nothing

with which to work. Those days of improvisation left not

only an ineradicable impression on our minds, but served as

the beginning of a strong attachment to this old place; which

already seemed like ours, for we were rebuilding it. We all

scrubbed and cleaned everything we saw; patients, beds,

equipment, decks and bulkheads. We had to work hard to

get our ship in commission.

The wards were scattered over a large area. Several wards

to a service required leaving the "Sister's Bunk" and penetrating

the darkened, icy corridor. This was increased in listened to the howling of the black cats and could practically

feel the presence of the Gray Lady."' · We dared not move

without a torch or a corpsman, for it was when you were

alone that she crept up behind and tapped you on the

shoulder. The Gray Lady was probably Queen Victoria herself,

who couldn't rest after the Americans came, and therefore

walked the decks at night to observe and protect. (I

have yet to see her, though I worked nights.) In the central

part of the building is a museum, which has not only stuffed

birds of every feather, but Queen Victoria's wheel chair and

shawl. The museum, the Gray Lady, the black cats, and the

nightly air-raids all seemed to form an integral part of the

atmosphere.

At the foot of every bed hung a gas mask and helmet,

which subconsciously held the attention of every patient at

the first sound of the air-raid siren. Most of them lay quietly

in bed, faces motionless, listening. Sometimes one would

get up and pace the floor; sometimes they'd ask for things,

little things like a glass of water or a cigarette. Mostly they

were mystified at the lack of display of emotion on our part, ·

and felt that we just did not know what it was all about. It

took superhuman effort to show them that we were concerned

and would take care of them, even though we had

not seen all the horrors of war that they had. It was not necessary

to become upset to realize and recognize danger.

Thus it was, slowly but surely we were gaining their confidence

for their care.

On June fourth, we heard the midnight broadcast announce

the fall of Rome. Two days later, the Germans released

this announcement: "The Americans have started

their Invasion."

We evacuated all our British patients to make room for

casualties. Some thoughts running through our minds at this

point were those of insecurity - "Are we ready to handle

the situation?" and "Can we give those fellows what they

need?"

The first days after D-Day caused a lull in everything.

Empty beds were ready; doctors, nurses, and corpsmen

waited; all activity on the water front ceased; a deadening

silence seemed to settle in the atmosphere and press heavily

downward. In the hush of the evening, if you went outside

and listened, you could hear the cannon-fire from the direction

of France. It wasn't long, however, before the results

of the Invasion were obvious, as LST's and hospital ships

returned, bringing the wounded with them. Never before did

I realize the horror of war surgery as exemplified by removal

of shrapnel and bullets, debridements, excision of large

amounts of young healthy tissue that had been exploded,

compound comminuted fractures, craniotomies, gas gangrene,

and amputations. It made your heart ache for these

young American boys whose sacrifice made ours look insignificant.

The fine spirit portrayed by these fellows was truly remarkable.

Their cheerfulness and adjustment to their infirmities shall not be easily forgotten.

On June fourth, we heard the midnight broadcast announce

the fall of Rome. Two days later, the Germans released

this announcement: "The Americans have started

their Invasion."

We evacuated all our British patients to make room for

casualties. Some thoughts running through our minds at this

point were those of insecurity - "Are we ready to handle

the situation?" and "Can we give those fellows what they

need?"

The first days after D-Day caused a lull in everything.

Empty beds were ready; doctors, nurses, and corpsmen

waited; all activity on the water front ceased; a deadening

silence seemed to settle in the atmosphere and press heavily

downward. In the hush of the evening, if you went outside

and listened, you could hear the cannon-fire from the direction

of France. It wasn't long, however, before the results

of the Invasion were obvious, as LST's and hospital ships

returned, bringing the wounded with them. Never before did

I realize the horror of war surgery as exemplified by removal

of shrapnel and bullets, debridements, excision of large

amounts of young healthy tissue that had been exploded,

compound comminuted fractures, craniotomies, gas gangrene,

and amputations. It made your heart ache for these

young American boys whose sacrifice made ours look insignificant.

The fine spirit portrayed by these fellows was truly remarkable.

Their cheerfulness and adjustment to their infirmities shall not be easily forgotten.

PREPARATION AND PREVIEW

Was "D" day in April, May, June, or July? We did not

know but the density of the shipping, the frequency of

alerts, the heavy A.A. fire all suggested that we might at any

time be called upon to receive casualties in large numbers.

Would we be, could we be ready? The problems of supply

and maintenance have been mentioned. There was also organization

and training. It was evident that, under pressure,

the surgeons would be fully occupied in the operating theatres

and in the surgical and orthopedic wards. This left the

sorting of casualties and the conduct of the care of burned

and shock patients and of the medical cases to be covered After conferences, arrangements were made that the triage

would be carried out in the passageway on the first deck by

the Chiefs of Medicine and Surgery, the Psychiatrist, the

Hospital Corps Duty Officer and a special crew from the

O.D., Record, and Personnel offices and that litter bearers

would be non-medical personnel. SOQ, Burn, and Shock

wards were accepted as a medical responsibility and from

this stemmed medical, surgical, and orthopedic SOQ, "23,"

and "51" and "52."

There were six qualified operating room technicians in the

complement. A school was established and instruction given

to an additional twenty corpsmen. A course in Anesthesia for Dental officers and Nurse Corps Officers was also developed

and we finally could activate eight operating teams,

simultaneously, each with surgeon, assistant, anesthetist, and

corpsman and with sufficient nurse supervisors and circulating

corpsmen. Instruction of corpsmen in the shock and

burn wards was carried out and teams of medical officer,

nurse, and corpsman arranged. On the other wards instruction

in technique and the use of equipment was given.

Drills, some in cooperation with Follands Aircraft, were held

until the "bugs" were eliminated, all hands could be called to

action stations and all had learned their duties.

The number of Dental, Hospital, Supply, Chaplain, and

Nurse Corps officers and of the enlisted personnel did not

change. On March 28, five additional Medical Officers reported

for duty, on April 21 Commander Churchman arrived,

and later three additional Medical Officers were assigned

for temporary duty. So there was a maximum of

forty-two doctors, ninety-eight nurses, twelve Hospital Corps

officers, four Dental and two each Supply and Chaplain

Corps. There were 585 enlisted men.

Was "D" day in April, May, June, or July? We did not

know but the density of the shipping, the frequency of

alerts, the heavy A.A. fire all suggested that we might at any

time be called upon to receive casualties in large numbers.

Would we be, could we be ready? The problems of supply

and maintenance have been mentioned. There was also organization

and training. It was evident that, under pressure,

the surgeons would be fully occupied in the operating theatres

and in the surgical and orthopedic wards. This left the

sorting of casualties and the conduct of the care of burned

and shock patients and of the medical cases to be covered After conferences, arrangements were made that the triage

would be carried out in the passageway on the first deck by

the Chiefs of Medicine and Surgery, the Psychiatrist, the

Hospital Corps Duty Officer and a special crew from the

O.D., Record, and Personnel offices and that litter bearers

would be non-medical personnel. SOQ, Burn, and Shock

wards were accepted as a medical responsibility and from

this stemmed medical, surgical, and orthopedic SOQ, "23,"

and "51" and "52."

There were six qualified operating room technicians in the

complement. A school was established and instruction given

to an additional twenty corpsmen. A course in Anesthesia for Dental officers and Nurse Corps Officers was also developed

and we finally could activate eight operating teams,

simultaneously, each with surgeon, assistant, anesthetist, and

corpsman and with sufficient nurse supervisors and circulating

corpsmen. Instruction of corpsmen in the shock and

burn wards was carried out and teams of medical officer,

nurse, and corpsman arranged. On the other wards instruction

in technique and the use of equipment was given.

Drills, some in cooperation with Follands Aircraft, were held

until the "bugs" were eliminated, all hands could be called to

action stations and all had learned their duties.

The number of Dental, Hospital, Supply, Chaplain, and

Nurse Corps officers and of the enlisted personnel did not

change. On March 28, five additional Medical Officers reported

for duty, on April 21 Commander Churchman arrived,

and later three additional Medical Officers were assigned

for temporary duty. So there was a maximum of

forty-two doctors, ninety-eight nurses, twelve Hospital Corps

officers, four Dental and two each Supply and Chaplain

Corps. There were 585 enlisted men.

On April twelfth a Red Cross Hospital Unit consisting of

the Misses Georganna Tucker, Lucy Chapman, Mary-Burton

Wallis, and Mildred Elmore arrived. Later, Miss Mildred

Talbot was added. These ladies immediately turned to and

developed the old Family Hospital into attractive and cheerful

recreation rooms with an additional space in the old gymnasium

on the third deck.

The railroad siding was made serviceable.

So it was not all work. There were dances for the crew to

which Wrens turned out en masse, ships' parties, officers

dances and a truly lovely Easter·"tea" given by the Nurses.

Movies, "ENSA," Red Cross and U.S.O. shows were held in

the Cinema. There were opportunities to visit Southampton,

Winchester, Salisbury, and Bournemouth. The "Pub" system

was thoroughly studied. The New Forest attracted some

for cycling or hiking and the packet steamer to the Isle of

Wight was a scenic trip. British friends were made and with

them an opportunity came to observe a way of life. Medical

officers visited the R.A.M.C. Hospital at Shaftesburyand the

R.A.F. center for Burns and Plastic Surgery at East Grinstead.

Army General Hospitals were seen and prior to the restrictions

of April first, trips to London for the day were

made.

At midnight on the fifth the patient census was 481. At

noon on the sixth the first hospital train pulled in and we

began to evacuate. A second train followed and these, with

duty parties, reduced the census to 206, making some 800

beds available for the reception of the wounded.

On the seventh and eighth no casualties were received although

the 10th was very active. On the ninth a few came

in and the census was 246. On the tenth it was only 312 and

we began to wonder if we were being bypassed. Shortly

before midnight on the eleventh doubts were dispelled as

ambulance after ambulance brought us the wounded from

"Utah" and bloody "Omaha" beaches. In twenty-four hours

we admitted over 400 patients, a figure we were to exceed on

September sixth and eighteenth, but these were the freshly

wounded in need of definitive care. The triage worked beautifully

and we admitted at the rate of better than one patient

per minute. "Medical IV," "G.U.," "51," "23," "Surgery I,

II, Ill, IV," "ENT' will long echo in the ears of those concerned.

On the wards the patients were put to bed, admission

slips made out, effects and valuables collected for the

bag room crew or the supply officers, doctors saw the patients

and instituted treatment, and the four-hourly reports of

evacuables were prepared. Commissary and galley crews

turned out to feed the hungry and they were fed, cleaned up,

treated and allowed to sleep. What a difference in appearance

there was between the patients in the sorting line and

on the next day!

During these early days the operating theatres were

manned continuously as only the occasional patient had received

more than First Aid and most were in need of definitive

surgery. In one thirty-six hour period 141 operations

were performed. As the doctors made sick call, lists were prepared

and sent to the theatres where four to five teams operlated steadily until the work was completed. Very few slept

more than a few hours between the eleventh and the thirteenth

and for several days thereafter it was sometimes necessary

to order personnel to bed for he or she would not stop

voluntarily while there was care to be given.

During June, 1838, July, 2009, and August, 1258 patients

were admitted, of whom 54% had been wounded m action.

Other patients were "combat" and "operational" fatigue, injuries

due to accident or disease.

British, Canadian, French civilians including one

woman sniper, in addition to our own Army, Navy, Coast

Guard and Merchant Marine personnel were received. On

two occasions, for about twenty-four hours, German prisoners

were segregated under guard and then transferred.

The patients were landed on the Southampton hards, distributed

by the Army, and sent to us by ambulance in groups

varying from fourteen to 397.

woman sniper, in addition to our own Army, Navy, Coast

Guard and Merchant Marine personnel were received. On

two occasions, for about twenty-four hours, German prisoners

were segregated under guard and then transferred.

The patients were landed on the Southampton hards, distributed

by the Army, and sent to us by ambulance in groups

varying from fourteen to 397.

The following notice was posted on 22 June:

"To"To All Hands:

The following excerpt from a letter received from Admiral

Harold R. Stark, Commander of the United States Naval

Forces in Europe, after his inspection of the hospital is

quoted for your information:

'Back in the office today, still thinking about the wonderful

work you all are doing at Netley. Of course, I needed no

first hand knowledge of this, but yesterday, to me, was really

an inspiring sight.

As you know, I got not one single complaint but only expressions

of appreciation and gratitude from all the men I talked to as to the treatment they had received from your entire staff.

It was evident to me that not only were the physical troubles at once being looked out for in the most expert fashion, but also that the high morale that was exhibited could only have come about by the manner and the cheerfulness with which doctors and nurses and corpsmen must be

doing their work, and which was reflected by the patients

themselves.

My heartiest, and I might even say, my humblest congratulations!'

The Commanding Officer congratulates all hands on the

splendid showing made.

C. J. Brown

Captain (MC) USN

Medical Officer in Command"

In any event, with the progress of our forces in France, alerts

became less frequent and ceased in early August: Other

changes occurred also. We were receiving fewer patients for

definitive care and acting as a collectmg center for Navy

patients and an evacuation hospital for both Army and Navy.

By the middle of the month there was much less work for all

and "scuttlebutt" circulated that we were to be relieved and

go to other duty. As is so often the case, the scuttlebutt

was correct, orders for officers came in and a few detachments

followed. Navy patients who would not be ready for

dutv within thirty days were evacuated, some by air, some

by ship. Some of our corpsmen flew back with their patients.

became less frequent and ceased in early August: Other

changes occurred also. We were receiving fewer patients for

definitive care and acting as a collectmg center for Navy

patients and an evacuation hospital for both Army and Navy.

By the middle of the month there was much less work for all

and "scuttlebutt" circulated that we were to be relieved and

go to other duty. As is so often the case, the scuttlebutt

was correct, orders for officers came in and a few detachments

followed. Navy patients who would not be ready for

dutv within thirty days were evacuated, some by air, some

by ship. Some of our corpsmen flew back with their patients.

Early in September the plans became more definite and we expected to be gone by October first. The first party from the Army General Hospital which was to relieve us arrivedon the fifteenth. There were more officers detached, several of whom flew back. On the twenty-third a large group of

officers, nurses, and corpsmen left in a train which also carried

patients. This left only the Commanding Officer, the

Exec, the Chiefs of Service, Departmental heads, half the

nurses and rather less than half of the corpsmen to follow the

next week after turning over to the Army.

All Medical Department

personnel, except Captains Brown and Miller, were ordered to various activities within the States. Captains Brown and Miller went to the staff of Comnaveu and the seamen ratings were assigned to an amphibious force. The Support Officers went to Exeter, and several Hospital Corps officers

to the Eighth Fleet.

After eight months and eleven days of commissioned service we had received and treated over nine thousand patients.

personnel, except Captains Brown and Miller, were ordered to various activities within the States. Captains Brown and Miller went to the staff of Comnaveu and the seamen ratings were assigned to an amphibious force. The Support Officers went to Exeter, and several Hospital Corps officers

to the Eighth Fleet.

After eight months and eleven days of commissioned service we had received and treated over nine thousand patients.

Snag 56 and United States Naval Base Hospital #12 are now

a memory. Your historian joins Admiral Stark, Admiral

Mcintyre and Captain Brown in a sincere -

-Well Done

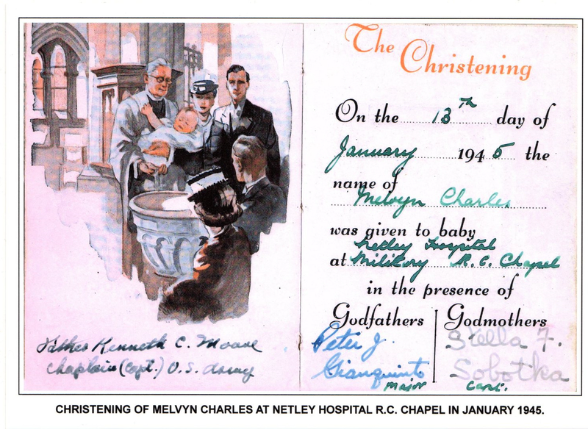

Christening of Melvyn Charles at Netley in January 1945

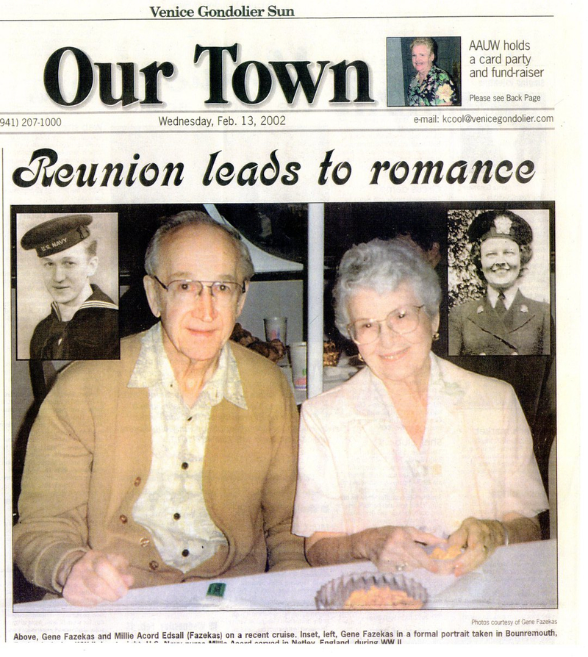

Gene Fazekas and Millie Acord Edsall

Some articles are from Netley Hospital Heritage archives.